LOOKING BACK ON BRIDGE OF SPIES AND LIFE BEHIND THE LENS

Young filmmakers all over the world take inspiration from the story of Janusz Kamiński. He left Poland behind around 1980 as a political refugee, studied at Columbia College in Chicago, spent a year at the American Film Institute, worked as a gaffer on no-budget Roger Corman films, and gained experience alongside future cinematography aces like Phedon Papamichael, Mauro Fiore, and Wally Pfister. Today, those peers recall that Kamiński’s eye and sensibility stood out even then as striking and personal.

Today, Kamiński is best known for work with Steven Spielberg, the duo having made more than seventeen major pictures together, including the visually bold Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan, as well as the forth coming West Side Story. Led by six Oscar nominations and two wins, his resume also includes fascinating diversions like Julian Schnabel's The Diving Bell and The Butterfly and the occasional foray into directing. Spielberg once said, “When I met him, I realized that there was a true artist standing in front of me.”

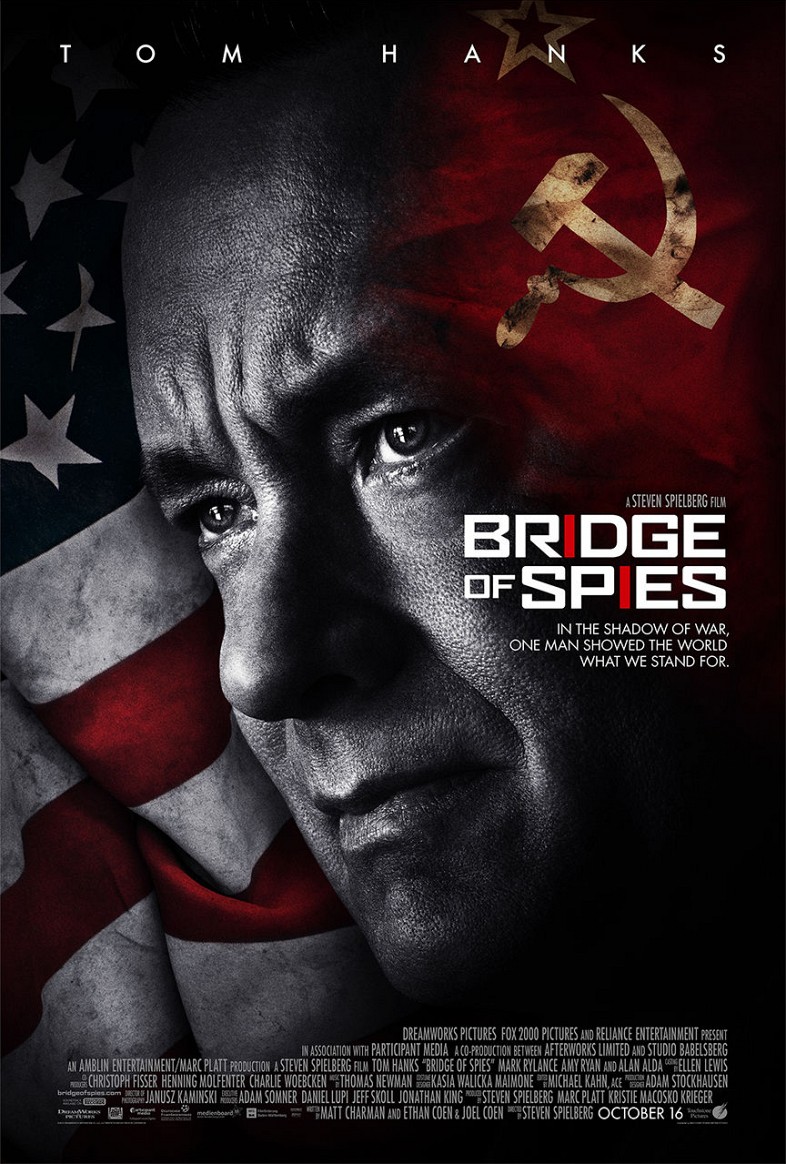

In a recent wide-ranging interview, Kamiński shares his thoughts about the state of cinematography and lensing, and how his personality informs his choices. He begins by looking back at Bridge of Spies, the 2015 Spielberg-Tom Hanks spy tale that unfolds in Cold War Berlin. He recalls the thought process behind his decision to shoot anamorphic using Hawk Vintage ’74 lenses and 35 mm film emulsion – Kamiński is well known as a passionate advocate for traditional film stock.

David Heuring: The advent of digital has engendered an explosion in lens choices, in part because digital sensors lack character, according to many. What was behind your decision to combine Hawk Vintage ’74 glass and film stock on Bridge of Spies?

Janusz Kamiński: It started with the desire to have the movie look a little bit different from other films I’d done. My experience previously was pretty much straightforward. I would manipulate the basic elements, or get some technical gizmos to alter the image, or alter the lenses without affecting focus.  I’ve done several movies with anamorphic, but my knowledge was very limited in terms of lenses – how they’re made, and things like that. I just knew that certain anamorphic lenses distort or soften the edges. But I didn’t really understand the optics that much. I’m always learning about these things.

I’ve done several movies with anamorphic, but my knowledge was very limited in terms of lenses – how they’re made, and things like that. I just knew that certain anamorphic lenses distort or soften the edges. But I didn’t really understand the optics that much. I’m always learning about these things.

For Bridge of Spies, because it was to some degree a political thriller, and a period movie, anamorphic seemed appropriate. I wanted to do something a little bit different, and play with the lenses. Someone suggested Vantage. I met the Hawk guys and they were just really great. I liked them, and I liked how accommodating and knowledgeable and attentive they were. Of course, almost all of the professional companies that support us are attentive – they have to be! This was right in the middle of the digital changes where people began trying to create more interesting visuals by using lenses and their distortions. I liked what the lenses were doing, but I wasn’t sure yet how much character and so forth I wanted. I had two sets, one slightly more conventional. And based on how they are made, they tend to have different types of flares at different exposures. Usually, the effect is more visible when you got to a lower f-stop. At higher f-stops, the quality becomes more conventional, but they never become 100% flawless. I had experimented with swing-and-shift lenses before, and I loved their ability to change focus within the plane of the lens. But these lenses were giving me an effect where the center was sharp and the edges were falling apart – but falling apart in a really nice way.

I really liked the tests. And I hate soft images. I have always had a strong dislike of how certain lenses resolve. I really don’t like lenses that are out of focus, unless it’s something I’m doing purposefully. These Hawk lenses are great because they resolve well across the field. There’s the distortion at the edge, but that means, depending on the composition, I can turn left or right to get more of the effect. That was really good for me. And the flares are really unusual. In that particular movie, we used the brightness of the light to tell the story. The East Germans are more obscure and sketchy, and the good guys, the West German world, is much brighter and cleaner. I used that approach throughout the movie, and it worked for me. The Vantage lenses have a very specific look. Since then I’ve seen them used really nicely in other films.

I’m not really that crazy about using lenses that are plastic or experimental. David Devlin is a cinematographer who used to work with me, and he’s very much into all these different lenses, which he tells me about. Everyone is making lenses now. Whatever allows people to achieve their results – great! I just think the most important objective of the lens is to keep it sharp. From there it’s about how the light travels, and then you can worry more about how it falls apart. But in the end, is the center of the lens sharp when you want it to be sharp? Everything else is less important to me. As long as I know how the lens will react, I can work with it.

DH: What’s your take on the use of unusual lenses in filmmaking these days?

Janusz Kamiński: The whole concept of creating the image has been changed in the last few years. There’s a reason people are using gimmicks in front of the lens to alter the image, and it’s simply because the digital images are so crispy, so unforgiving. That’s the main reason why people are shooting at very shallow depth of field, with soft light, and putting crystals in front and shooting through things. They are trying to achieve an image that’s not so sterile. Everyone wants so-called cinematic storytelling. Where really, we had that before. There was really no reason to change from film into digital. But that’s another story.

I don’t mind messing around with the lenses, but I’m not really that person who would put crystals in front of the lens. But I still work with film, so the aesthetics are different. Cinematographers do achieve beautiful results by shooting through crystals or putting piece of glass in front of a lens. But these are not new tricks. All those tricks are well established tricks from the past. The ability to use what has been done in the past to your advantage, to create a more interesting image – that’s a strength. Often, it works. And often it doesn’t. You wonder – what are we doing here? What is the point?

Look at a very underrated movie called In the Cut, directed by Jane Campion and shot by Dion Beebe. Dion did amazing work in that movie with the swing-and-shift. It was just so interesting and stimulating and accurate for the storytelling. And then those lenses disappeared from moviemaking. I occasionally use them because I love them. But putting things in front of the image is tough to do well, because you’re taking a very strong point of view. But the downfall is that so many young cinematographers don’t know how to light. They put the camera up, they see the image. They crush it or whatever they do. They don’t use light. Now they are looking for some excitement, some gimmick that might work. But to me, excitement comes from lighting and composition and all that stuff. I do think things are getting better. It’s not necessarily beginning to look like film, because that aesthetic doesn’t exist anymore. It just looks like digital. But there’s this need to manipulate the image somehow.

I was just looking at a series from 2016 on HBO, directed by Robert Zaillian, called The Night Of. Robert Elswit shot the pilot and one other episode, and other episodes were shot by Fred Elmes and Igor Martinovic. It’s about a Pakistani-American kid who gets wrongly accused of a violent murder. I was amazed. It’s so beautifully shot, lit and composed. It’s the opposite of the gimmicky approach. I think today, people go to the movies because they tend to want to gimmicks. People use that approach because it works for them. They shoot at a very low stop. I can’t make movies like that with Steven because we make very specific movies, “movie” movies. You’ve got to keep it as sharp as possible. West Wide Story is a bit different. We shot at a very heavy stop because we wanted all the people to be sharp at all times. With dancers moving through space, there’s nothing worse than shallow depth of field. My point is that the knowledge is the knowledge, and the gimmicks are the gimmicks. There are gimmicks that don’t work, but when the gimmicks are working, you’re brilliant, right? I’d probably do it if I could make them work for me.

DH: But the choice of lenses can be a more subtle, subconscious, less literal way of imbuing the overall image with a certain flavor, right? The effect doesn’t have to be so strong that it becomes a gimmick. To me, Bridge of Spies works because of a feeling of unnamable dread that works with the claustrophobic spaces and dirty light. How do you know how much flavor is too much? How strong to make it? When to stop? You gave me a quote a long time ago – “To what extent do you stylize the movie without going too far and becoming noticeable? That is always the biggest question.” I guess that’s what I’m asking, and the answer depends.

Kamiński: It’s true in every artform – how artistic can you become without taking it too far and ruining the audience’s experience? We have to do several things at once. You can’t just say “I like it because I like it,” unless you’re Jackson Pollock. You look at his paintings, and you say, “What the fuck is that!?” Unless it looks pretty, people tend to dismiss it. And then you start learning about it, you realize the context and the evolution, how it came to be, and you begin to appreciate the beauty of the art. But that’s very complicated. Movies are much simpler. Am I taking the audience away from the movie or am I bringing them more in? It’s as simple as that. When to use it, when not to use it is driven purely by the story, not by the desire to be gimmicky. But I think everyone in moviemaking comes from that principle. The older directors had a saying, that there’s only one place to put the camera – the right place. How ambiguous and phony that sounds! But in fact, it is true. But that all falls apart when the camera moves. When is camera moving? Why is the camera moving? What is the purpose of the movement? So there has to be a purpose for everything.

In the movies of the 1960s and ‘70s, they would put a kit so the lens for a kaleidoscopic effect. That was the psychedelic times. Then the ‘80s were clean. The ‘90s became almost nothing there. And then we entered a slightly more interesting stage in terms of images, because now, whatever you see, you get. Because of digital, you can push the storytelling in a direction that before would have been risky. So subsequently the new gimmick is to be really dark, and all the colors are a little bit pastelish now. The new thing looks like the way Robbie Müller shot The American Friend – all those saturated warm tones, and very soft in the lighting. They’re not inventing anything new. They just copy things.

DH: Do you have an opinion on current trends in terms of image contrast?

Kamiński: One great advantage of digital is you can go as dark as you want. And you can go as bright as you want, as long as the people around you accept the aesthetic. So you see things that are very dark. You think, “Wow, what’s going on here? Is my TV too dark?” No – that’s the style. That’s a gimmick to me. I don’t understand it. I like some brightness in images. But brightness and darkness means contrast. But people do it because they can, and a generation is beginning to accept that. In Saving Private Ryan, for example, we had a very clear approach. It’s a war movie, and it’s supposed to feel realistic to the audience. It would never be like documentary. But the older, wide-angle lenses I used were less contrasty, and not perfect. They were dirty, and the flares were not perfect. I did some tests, and what we learned was very beneficial for the storytelling. OK, good, I got the lenses figured out. I know what I’m doing. I also knew that I was going to introduce more contrast later in ENR process, so I didn’t mind that the lenses were lower contrast. Right now, that’s a concept that does not apply whatsoever in my opinion to digital photography. You can alter the contrast with the computer to get whatever you want. So, the idea of choosing lenses for the sake of having low contrast is a gimmick. It works for people, that’s fine. But you’re getting very flat image to begin with. You’ve got flat lenses, so now you have a problem built into the system, a system that will give you a little bit more contrast later, which is insane.

With The Driving Bell and the Butterfly (2007), it was written in the script. Jean-Dominique Bauby wrote that amazing story, and Ronald Harwood wrote the script, but they and Julian Schnabel wouldn’t tell me how to do it, how to find the light. The script said that the patient comes out of unconsciousness slowly and the world is revealed in images that he cannot recognize at first. Well, that’s very nice description. But I’m going to have to create that visually. So I started playing with all kinds of things – lenses, swing-and-shift, ways of being out of focus on purpose. I realized that it worked for me, but I also realized that you cannot sustain the story if you continue the same approach throughout the course of the entire movie. And clearly the movie allows for being conventional in many situations from other people’s perspectives. So, everything from his perspective was one way. Anything from other people’s perspectives was another way. So, to the question of when and how do you apply the idea of altering the image visually, destroying the perfection of the image, the answer is that it comes from the necessity of the story.

DH: I understand that it comes from the imperative to serve the story, but that doesn’t address how you know when something is overdone, or strong enough to be effective and fresh without taking viewers out of it, which you see all the time in cinematography, especially given today’s ability to do almost anything. I guess it’s called taste.

Kamiński: How do you know when it’s working? I have no idea why I like this color or that color or why I like the sky with this cloud or that cloud. That’s just individual interpretation of the world around you. As a society, human beings have a herd mentality. I’ve always felt a sense of being different, of not belonging. I’m just wired in a different way. I don’t have an ability to blend in, and in fact I have often felt handicapped by this. When I go to a restaurant, and I ask how the fish is, and they tell me it’s very popular, I say, “Fantastic. Bring me the unpopular dish.” I have never wanted to be part of the class. When it comes to socializing, I always make the awkward comment. Someone asked me. “When was the last time you were embarrassed about something?” Every day, for my entire life. So I run away from the mundane. I do not dismiss those who tend towards the similar as lesser or better! I just don’t want any part of it.

So how do I make a choice? I have no idea. I can speculate. You make choices based on the story and your interpretation of the story. And your interpretation of the story comes from being wired a certain way and having a very strong point of view that is unique to you that makes you see the world a different way. If people like and accept how you see the world, then you are considered good and called unique. If they don’t like how you see the world, you are schizophrenic, and you’re put in a special institution because your point of view is different. At best, you are merely eccentric and strange.

DH: One topic we always return to is the control over the image and how to keep it in the hands of the director of photography despite the ever-changing technology of filmmaking. Some filmmakers I’ve interviewed have asserted that as digital cameras and the related tools have matured, this is less of a problem, and that image fidelity is more consistent. It’s not being used as a way for other people to get a hold of your image and change it against your wishes. You usually work in an unusual situation compared to most cinematographers, given your partnership with Spielberg, the respect that you command, and the fact that you shoot film. But do you think it’s true that cinematographers are now able to exert a degree of control over their image closer to what they used to have in the film days?

Janusz: Of course it depends on the project. Every time I do anything outside the movies I do with Steven, I spend countless hours and money to assure that there’s consistency and to preserve the image. You’ve got a great image, and then the moment the image goes into any visual effects process, it’s fucked. They seem to completely disregard your intent. On the top of your image they splatter their own shit. They alter the image and then you have a really hard time to go back where you were. That is constantly the case in terms of commercials. I have a great guy who works with me in commercials. I’m 90 percent there, and then it goes into effects and they do their own interpretation. Suddenly, everything is yellow. That’s the most frustrating thing. I’m fortunate to work with a DI colorist who knows my aesthetics. But it’s difficult to get to that position. It used to be five or six stops, and red, green and blue, there in the negative. Now, you can create a look, but that look can be altered because the files are delivered raw anyway. Is the solution to bake it into digital files? Perhaps, but I don’t know how to do that.

Several months ago I was doing the color timing on Call of the Wild, and every time there was visual effect, the image was different. The visuals effects were very good! But then my stuff doesn’t look good. Why are they unable to maintain the visual originality of the image that they were provided? That’s the problem. It’s not a lack of respect. It’s a lack of some kind of continuity between what I see when I do my colors and expose it, and the next person who sees it on their own system. The results become average. It’s not a problem of controlling data. It’s the problem of having the ability to maintain continuity.

Images: Vantage Film, Janusz Kamiński Photo by Jaap Buitendjik, ©2015 Twentieth Century Fox