CLASS-X AND COLOR ON THE MAN WHO SOLD HIS SKIN

Christopher Aoun’s second narrative feature film, Capernaum, made a strong impression, winning the Cannes Jury Prize, a German Cinematography Award and an Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Film. His follow-up feature film, The Man Who Sold His Skin, debuted at the Venice Film Festival in September 2020 and brought him another Oscar nomination for Best International Feature in the 93rd issue of Academy Awards.

The new film has a unique inspiration – it’s drawn from a living work of art titled “Tim,” created by the Belgian artist Wim Delvoye. The main character, in a desperate bid to rescue his fiancée, agrees to have his back tattooed as a Schengen visa. Soon his body is turned into a living work of art and exhibited in a museum. He achieves a kind of freedom, but it comes at a price.

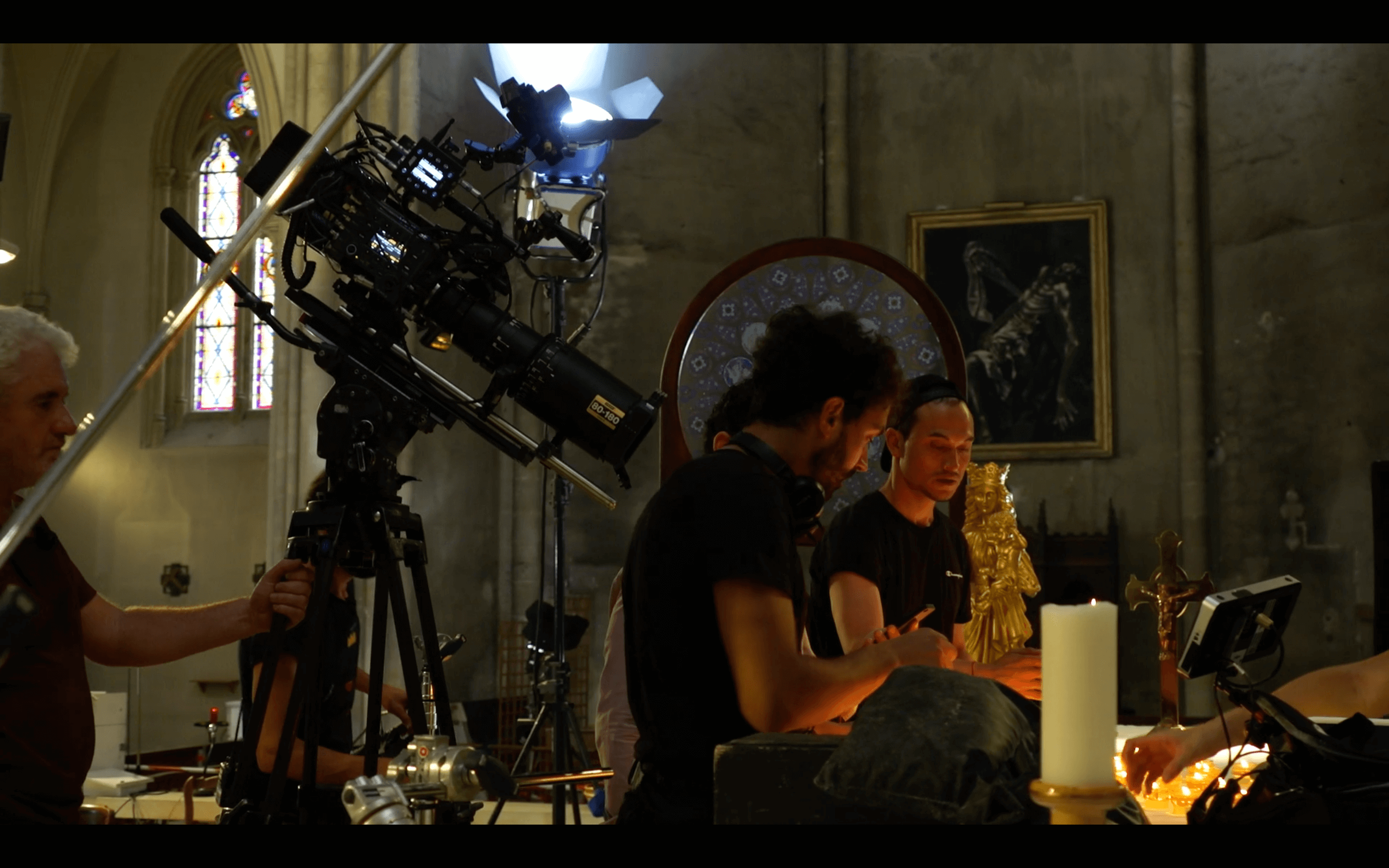

To photograph this extraordinary tale, Aoun chose Hawk lenses, as he did on Capernaum. This time, however, instead of Hawk C‑Series Anamorphics and Arri Alexa, he opted for Hawk class-X Anamorphics combined with the Sony Venice camera. The camera was set to 4K resolution using an anamorphic 4:3 image area.

“Capernaum was very documentary and character-driven,” explains Aoun. “For The Man Who Sold His Skin, it was the opposite. We’re not in a realistic world. It’s a world I wanted to aestheticize or change into something, which is my profession, sort of like the artist putting the tattoo on the character’s back. It’s visually more interesting for me to change the reality based on how I feel. The character’s head is his own, but his body, and everything around him, is no longer part of him.

“So with that in mind, I tried to create throughout the movie different textures and colors using filtration, and the focal lengths and movement is always changing,” he says. “Sometimes I had as many as seven or eight filters on top of each other. So in terms of the lenses, I needed sharpness almost like a spherical lens, but not spherical. The class‑X gave me that sharpness. It was like a blank page where I could play with my filters and maintain crispness in a way I couldn’t with any other anamorphic lenses.

“Meanwhile, the lenses were giving me a nice bokeh, another element to play with,” he says. “We often used the close-focus ability, which is unusual in anamorphic lenses, and I also liked closing down the stop and manipulating the edge distortion. I just love the look.”

The camera is generally objective, but Aoun sometimes varied focal lengths to represent the point of view of different museum-goers. “The class-X set ranges from 28mm to 140mm, and we also had the 80-180mm with one extender. In previous films I almost never went over 80mm, except for landscapes or special shots. Here, I went up to 360 mm and I also used the 28mm a lot. Sometimes with the very long lenses, I’d stop down just to create graphical patterns coming into each other, really playing with composition and layers, but in a more violent way than usual.”

The interaction of the filters, the lenses and the sensor at the moment of photography was important to Aoun. “I didn’t want to add these effects later,” he says. “I wanted to have the movement start with the flare coming from exactly this or that position. I also used a lot of diopters. You might call these very old techniques, but what I was looking for was something organic, with patterns on the sensor that move the way film grain moves. It’s just different than having a clear lens shooting on the sensor and then adding effects later on.”

The Hollywood Reporter review of the Venice screening praised the film’s bold imagery, noting that “the title was shot by ace cinematographer Christopher Aoun, who was responsible for the ravishing visuals of the Oscar-nominated Lebanese feature Capernaum and whose painterly work here is equally impressive.”

Looking back on the shoot, Aoun says, “I know that in some way I risked it all. It could have been a disaster. But it was a great experience to learn so much and mix those visual elements with the story. I’ve always been one of those who says that the cinematographer has to stay in the background and serve the story. But in this case, it was really about the cinematography framing those pieces of art. It was really fun for me to have that motivation. I didn’t feel like I was overdoing it, because it was in a context that allowed me to go for it.”

Watch trailer here.

images: Christopher Aoun/Vantage Film/imdb